Dark Horse VS Prodigy

ST57: Seven Things on New Year’s resolutions, trail design, interior designing AI, and more

🎇Happy New Year!

How did you celebrate, if at all? This year, it was rather anti-climactic at our home. Infants don’t care about calendar dates and require the same routine no matter what the circumstances. So we kept it low-key, pouring our pewter and exchanging a few late Christmas gifts before drifting off into sleep to the background noise of London erupting into cascading explosions at midnight. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

I wish you an amazing 2023 with plenty of inspiration and time for deep thought and creative pursuits. To kick off the year, here’s what I wanted to share with you:

One — A story about what early childhood might reveal about ordinary people’s futures

Two — Seven Things on New Year’s resolutions, trail design, interior designer AI, and more.

1. How To Find Your Path If You're Not A Child Prodigy

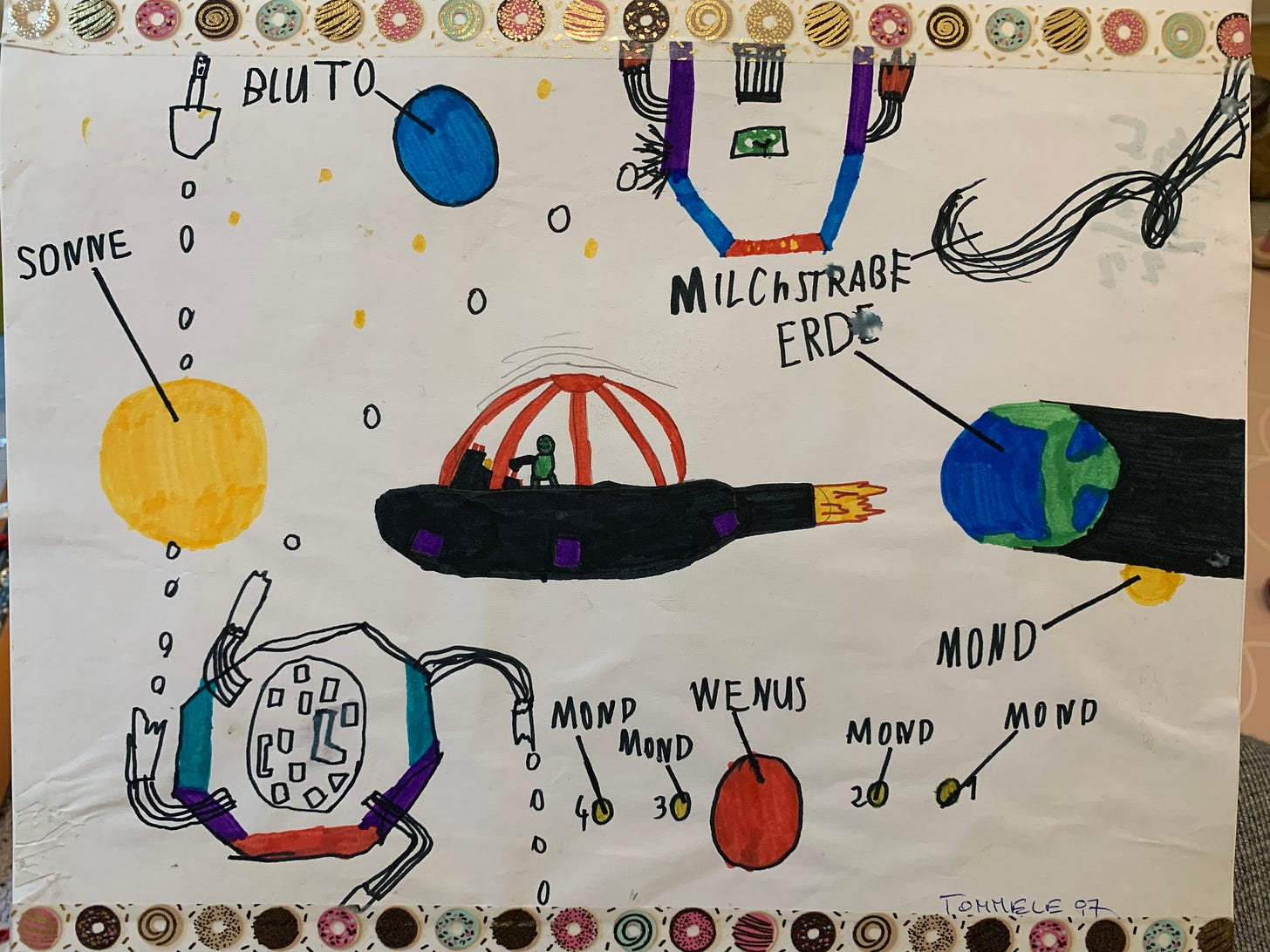

This Christmas, my mum surprised me with a special gift she had made herself. Or rather, I had made it. Throughout my childhood, she had collected every scrap of paper I scribbled or wrote on, poured wax over, or stuck other materials to. Over the past few months, she had painstakingly gathered it all together into two albums. They represent a snapshot of my earliest years through my own childish eyes - each page brimful with happiness, dreams, trauma and all the other elements of childhood.

I never felt as though I knew exactly what to do with my life. While I am fortunate with how it turned out so far, I'm still open to pointers on where my next step should take me. When I was gifted the collected works of little Tommi Essl, I spotted an opportunity: Might this look into my deep past provide such directions?

Listen to any one celebrity role model, and they'll have a story about how - when they were little more than toddlers - they composed a concert, were natural ice skaters, or coded an operating system from scratch. Granted, there are a handful of geniuses in every generation who are unusually talented from birth. But where does that leave the rest of us? If we haven't already dedicated our lives to one skill which revealed itself early on, how should we find a north star to guide us through our futures? How will we learn what vocation to pursue and which talents to nurture?

In his book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialised World, David Epstein doesn't just give solace to those whose destinies didn't manifest early but argues that they're actually better off this way:

»Generalists often find their path late, and they juggle many interests rather than focusing on one. They're also more creative, more agile, and able to make connections their more specialised peers can't see."«

Rather than being chosen by one particular talent, generalists turn into dark horses, nimbly defining their path as they go:

»Dark horses were on the hunt for match quality. "They never look around and say, 'Oh, I'm going to fall behind, these people started earlier and have more than me at a younger age,'" Ogas told me. "They focused on, 'Here's who I am at the moment, here are my motivations, here's what I've found I like to do, here's what I'd like to learn, and here are the opportunities. Which of these is the best match right now? And maybe a year from now I'll switch because I'll find something better.'"

Each dark horse had a novel journey, but a common strategy. “Shortterm planning,” Ogas told me. "They all practice it, not long-term planning." Even people who look like consummate long-term visionaries from afar usually looked like short-term planners up close.«

(For more about David's ideas, subscribe to his newsletter

)Once you've made your peace with not having a singular destiny and taken an approach of short-term planning instead, one question arises: How do you then go about making such short-term decisions?

I was overcome with emotions and memories when leafing through my childhood 'artwork'. Still, there was another feeling: disappointment at how utterly unremarkable the works themselves were, how unskilled the execution. Crucially, there didn't seem to be an indication of any one particular skill or interest. I drew just as many boats as I did houses, sheep, stars, and planets. A fact sheet which a Tom who was just learning to write had penned stated that I was going to be either a poet, or a sheep herder. If there was anything, in particular, this young boy should be focusing his energies on throughout the life he was to live, there was no serious clue to be had here except that it should not be art.

I said this to my dad, who didn't seem worried. He thought I'd been looking for too literal a clue. Across all the works, he spotted a pattern: When I drew a boat, I seemed more concerned with the rigging of the sails than a beautiful coastline. My dreams of tree houses may not have been those of a visionary, but they included precise floor plans. Other drawings of family activities emphasised how the stick figures interacted with the objects around them. And in any case, I was generally more interested in constructing and taking apart things, than drawing. In other words, child-me had focused on making sense of the world and how the objects that occupied it functioned, how man-made things could improve a person's (mostly my own) life.

The profession I'm in today did not exist when I made those drawings. But I did study mechanical engineering, followed by design. I still work on how to make technology as intuitive and well-functioning as it can be. As my remit has expanded with the years, I am more interested in understanding and defining the mechanics of how I can help teams of designers and technologists do their best work and how to make product organisations function.

Ultimately, I could have taken many paths aligned with what I could see in my childhood drawings. Had I become an architect - as I seriously considered at one point - I would have found the tree-house floor plans to be clear early confirmation of that path. It's a similar story had I stuck with mechanical engineering.

Does this mean that considering my earliest interests is a meaningless act of post-rationalisation? I think not. Instead, it means that in an ever faster-moving world where career possibilities shift and evolve rapidly, it becomes more important to look for and interpret the themes that run through all our passions. Early childhood is as good a point to start looking for them as any. These values then become the guard rails for making shorter-term decisions when navigating that ever-shifting landscape of opportunities.

A look into the past can tell us much about ourselves and our future, even if it is not by revealing one particular talent. When interpreting that past, it helps to consult those who may know us better than we do ourselves.

2. Seven Things I thought were worth sharing

Personal Growth: Given the time of year, I thought it appropriate to re-share an article on Goals that are bad for you

Creator Showcase: Illustrator Tonči Zonjić’s Not/But comic series gives you prompts for changing your thought patterns for the better

Design: As someone working in a field of design, it continues to amaze me how many ‘design’ professions there are. When hiking through Vermont last October, I learned about Trail design

Art: If you’re in London, head to the Cézanne exhibition at the Tate Modern. If you are not, browse some of his art in high-res online

Tech/AI: Israeli start-up creates virtual interior designs with AI

Data Visualisation / Sustainability: Not that I’m a fan of doom-scrolling, but for a creative piece of data visualisation, watch the climate spiral out of control

Fun/Entertainment: Phrase me is a site for cinema archaeologists or anyone else who is looking for specific phrases in films - to make a fun compilation, say.